Abstract

This study critically examines the delegation of Indonesia’s sovereign airspace, specifically the Flight Information Region (FIR) long managed by Singapore, as reaffirmed in the 2022 bilateral agreement. Although formally framed as technical cooperation in air navigation services, this arrangement raises profound questions of state sovereignty, defense, and political consistency. Drawing upon Jean Bodin’s theory of absolute sovereignty, C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite theory, and Graham Allison’s decision-making models, this study situates the FIR issue within a broader context of elite-driven policymaking and bureaucratic compromise. Complementing these perspectives, the legal doctrines of Professor Pablo Mendes de Leon and Professor Atip Latipulhayat underscore sovereignty as both a legal tool and a structural framework built upon three pillars, control of the air, use of airspace, and law enforcement.

The findings reveal that the FIR arrangement represents more than a technical aviation matter. It symbolizes the persistence of colonial legacies, the inconsistency of Indonesia’s national policy, and a deficit in the nation’s independence. By framing the FIR as a manifestation of neo colonialism in contemporary air governance, this study advances a novel interdisciplinary analysis that bridges political theory, international law, and air defense studies. It concludes that Indonesia’s independence remains incomplete as long as portions of its airspace are managed by foreign powers, challenging the Republic’s constitutional mandate to exercise full sovereignty for the welfare of its people.

Disclaimer

This study is an academic work prepared for the purpose of scholarly research and debate. The arguments, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the official policies or positions of the Government of the Republic of Indonesia, its ministries, or related institutions. References to agreements, treaties, and legal instruments are made for analytical purposes and should not be construed as legal opinions or official statements. Any errors of fact or interpretation remain solely the responsibility of the author.

In 2022, the Government of Indonesia and Singapore signed an agreement reaffirming the delegation of a portion of Indonesia’s sovereign airspace to Singapore, an area long designated as the Singapore Flight Information Region (FIR). While this agreement was formally framed as technical cooperation in air navigation services, the substance at stake is far more fundamental, Indonesia’s sovereignty over its national airspace.

The history of this arrangement stems from the colonial period, when British aviation authorities in Singapore and the Dutch colonial administration in Batavia divided responsibilities for air navigation services in Southeast Asia. This colonial arrangement persisted after Indonesia’s independence, leaving parts of the country’s western airspace under Singapore’s control.

In 2015, President Joko Widodo issued an unequivocal instruction, Indonesia must reclaim control of the FIR above its sovereign territory. Yet seven years later, the 2022 agreement once again extended this delegation, with the government citing technical readiness and diplomatic considerations. This paradox raises a critical question, can a sovereign state justify surrendering control of its own airspace to another country?

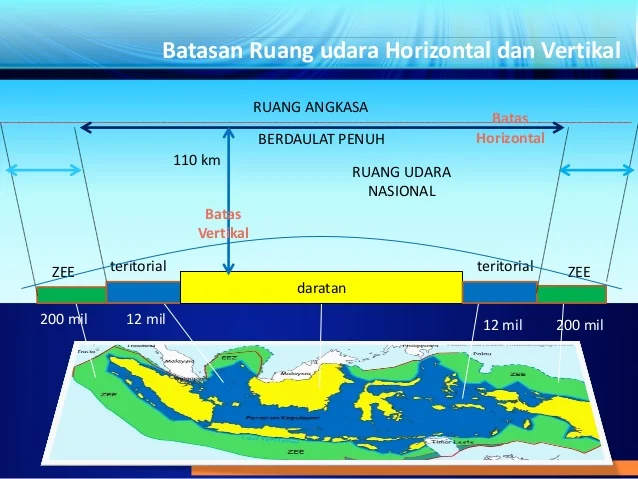

The Concept of Air Sovereignty

Since the Paris Convention (1919) and the Chicago Convention (1944), international law has affirmed that sovereignty over airspace is complete and exclusive.1 For Indonesia, the continued delegation of its FIR raises serious concerns in three domains, law, politics, and defense.

Three theoretical frameworks illuminate this problem. First, Jean Bodin’s theory of absolute sovereignty defines sovereignty as the indivisible and permanent authority of the state. Second, C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite theory explains how strategic national policies are often shaped not by public will, but by a small circle of elites. Third, Graham Allison’s decision-making models provide a lens to analyze why governments often arrive at suboptimal or compromise outcomes.

Complementing these perspectives are the contributions of international air law scholars. Professor Pablo Mendes de Leon underscores sovereignty as a critical legal instrument for safeguarding state authority over airspace, while Professor Atip Latipulhayat identifies three inseparable pillars of sovereignty control of the air, use of airspace, and law enforcement.3

Theoretical Perspectives

Jean Bodin (1530–1596), in Six Livres de la République (1576), emphasized that sovereignty is absolute, indivisible, and non-transferable.4 Thus, the delegation of Indonesia’s FIR to Singapore directly undermines the essence of sovereignty. Airspace is not merely a matter of technical air navigation, but the state’s ultimate right to regulate, utilize, and defend its territory.

C. Wright Mills, in The Power Elite (1956), argued that policies in modern states are often dictated by small groups of elites in politics, the military, and business.5 The FIR case exemplifies this, as the decision to delegate control was not the product of public deliberation, but of elite negotiation.

Graham Allison’s Essence of Decision (1971) proposed three models of decision-making, Rational Actor, Organizational Process, and Governmental Politics.6 Applying these to the FIR case reveals that the 2022 agreement was not a purely rational choice to enhance national security. Instead, it emerged as a bureaucratic compromise and diplomatic bargaining chip, particularly since FIR discussions were tied to unrelated issues such as extradition and defense cooperation treaties.

Legal and Political Dimensions

Professor Pablo Mendes de Leon stresses that reliance on sovereignty serves as a legal mechanism to safeguard airspace and national security.7 When Indonesia cedes part of its FIR, that legal safeguard is eroded.

Professor Atip Latipulhayat outlines three interdependent pillars of sovereignty, control of the air, use of airspace, and law enforcement.8 In practice, Indonesia cannot fully exercise any of these in the Singapore FIR, rendering its sovereignty incomplete.

Politically, the decision reflects inconsistencies within Indonesia’s own governance. Despite a presidential instruction in 2015 to reclaim the FIR, the 2022 extension contradicts this directive. Moreover, by placing FIR negotiations under the Ministry for Maritime Affairs and Investment, an institution without direct authority over airspace, rather than the Ministry of Defense or Transportation, the government weakened its own institutional coherence.

Problem Statement

The delegation of Indonesia’s FIR to Singapore represents more than a technical arrangement. It symbolizes:

- A contradiction of international law, which affirms that sovereignty over airspace is both complete and exclusive.

- An inconsistency in Indonesia’s national policy, where presidential directives are undermined by subsequent agreements.

- The persistence of a colonial legacy, where arrangements dating back to British and Dutch colonial administrations remain in place.

- A deficit in Indonesia’s independence, as the nation cannot fully exercise control, utilization, and enforcement of law over its own airspace.

These issues underscore that Indonesia’s independence is not yet comprehensive. As long as foreign powers retain control over portions of its airspace, Indonesia remains trapped in the remnants of colonial governance, raising profound questions about sovereignty, defense, and national dignity.

Conclusion

From the perspectives of Bodin, Mills, and Allison, combined with the legal analyses of Mendes de Leon and Latipulhayat, the delegation of Indonesia’s FIR cannot be justified. It contradicts the concept of absolute sovereignty, represents elite-driven policymaking, and reflects bureaucratic compromise rather than rational national interest. Ultimately, the continued delegation of Indonesia’s FIR demonstrates that the Republic’s independence remains incomplete. Sovereignty over airspace is not merely a technical matter of navigation, it is a core element of statehood. As long as portions of Indonesia’s skies are controlled by another state, the promise of full independence remains unfulfilled.

The continued delegation of Indonesia’s sovereign airspace, embodied in the so-called Singapore FIR, is nothing less than a living reminder of colonial procedures carried into the present. It exposes the inconsistency of our nation’s commitment to stand firmly against every form of domination. For Indonesia, the fight is not yet finished: colonialism and imperialism, together with their modern faces, neo-colonialism and neo-imperialism, must be confronted and eradicated once and for all.

References

- Allison, G. (1971). Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Bodin, J. (1576). Six Livres de la République. Paris: Jacques du Puys.

- Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, 1944.

- Latipulhayat, A. (2020). Kedaulatan Negara di Udara: Perspektif Hukum Udara Internasional dan Nasional. Bandung: FH Unpad.

- Mendes de Leon, P. (2017). Introduction to Air Law (10th ed.). The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

- Mills, C. W. (1956). The Power Elite. Oxford University Press.

- Paris Convention on Air Navigation, 1919.

Footnotes

- Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, 1944, Article 1; Paris Convention on Air Navigation, 1919. ↩

- Mendes de Leon, P. (2017). Introduction to Air Law (10th ed.). The Hague: Kluwer Law International. ↩

- Latipulhayat, A. (2020). Kedaulatan Negara di Udara: Perspektif Hukum Udara Internasional dan Nasional. Bandung: Fakultas Hukum Universitas Padjadjaran. ↩

- Bodin, J. (1576). Six Livres de la République. Paris: Jacques du Puys. ↩

- Mills, C. W. (1956). The Power Elite. Oxford University Press. ↩

- Allison, G. (1971). Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ↩

- Mendes de Leon, P. (2017). Introduction to Air Law. ↩

- Latipulhayat, A. (2020). Kedaulatan Negara di Udara. ↩

Jakarta , September 24, 2025

Chappy Hakim

Founder & Chairman Indonesia Center for Air Power Studies